“Even now that we see each other through a screen, our gaze plays a major role in the conversation,” says Chinmaya Mishra (34). “The way you look away when you ask a question tells me that you are thinking about your wording and I understand that I should not interrupt. If we were to stand at the coffee machine at the same time, we would largely coordinate our movements with our gaze. You first look at the coffee cup, then you move your hand. Just because you look makes me wait a moment, otherwise there will be coffee everywhere. Interpreting each other’s gaze is very important in communication.”

But how do you ensure that a robot also masters this subtle human behavior? On that question, Mishra received her PhD from Radboud University in Nijmegen on April 17.

A look at the scientific literature gaze called, consists of a combination of eye and head movements. During a conversation, someone often turns their head away for a moment. A robot that does not do this comes across as a staring conversation partner, highly uncomfortable. While social robots are intended to make contact with people. “A robot is a social robot if people are intended to interact with it,” says Mishra. “He doesn’t have to look like a human being, the main thing is that he is expected to participate in social norms.”

A robot learns this from data from human conversations. “We know, for example, that a person’s gaze moves to the object about 1,000 milliseconds before he or she utters the word,” says Mishra. “And that, as a conversation partner, I look at it 200 milliseconds after speaking. With help from a deep learning model the robot learns these types of patterns, so that it can also apply this knowledge in new situations. Many of these types of models are running at the same time in the robot. It is also very basic to recognize whether a person is present.”

Fond of computers

As a child, Mishra was not yet a robot madman. He was particularly fond of computers, so he studied computer science. He also wanted to learn about AI, but that subject was not offered at his Indian university. After three years of working as an IT consultant, he was given the opportunity to study AI in Germany. It wasn’t until he came to a robotics lab for a course that the spark flew. “There they worked with the predecessor of Ameca, the robot that also appeared in the film I, Robot with Will Smith is used. It is a full body robot, with a face that can also express emotion. Then I was captivated.”

The timing turned out to be good. Robotics and AI are in recent years boomingpartly thanks to the rise of large language models (LLMs), the type of computer model that is also behind chatbot ChatGPT. As a result, robots have quickly become more proficient in language and comprehension. “I was lucky that this happened during my PhD,” says Mishra. “Previously, robotics models were more focused on the specific robots for which they were developed. Thanks to LLMs, what we make is more universally applicable. My goal has always been to make things that can be used by everyone.”

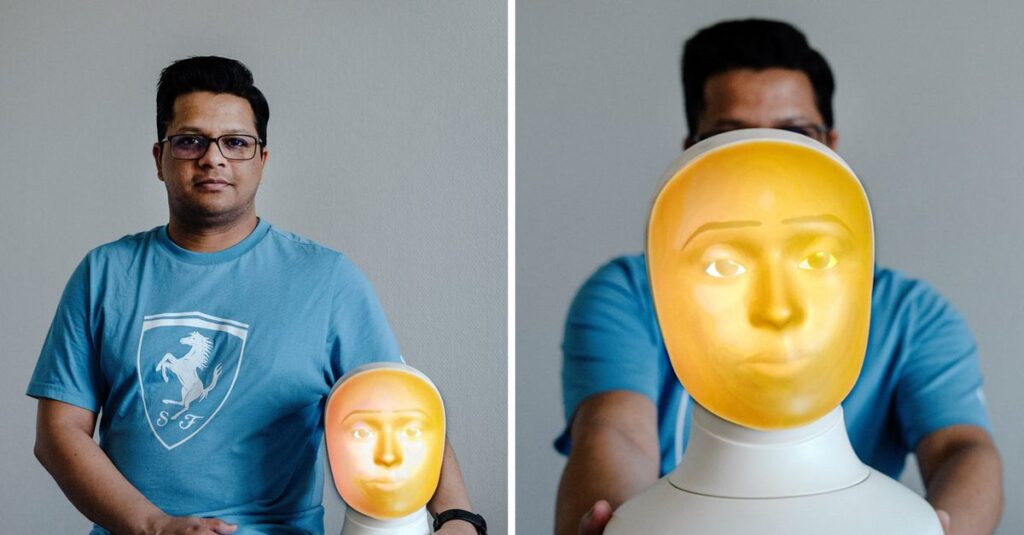

The robot Mishra worked with during his PhD, called Furhat, only has a head. A face has been projected from the back, allowing him to have nuanced expressions. To investigate whether the communication feels lifelike, Furhat played a card game with two people. “Five cards with images were shown on a touchscreen,” says Misha. “A question could be: you have to survive in the desert, sort the five images in order of usefulness. The three interlocutors discussed this.” Indeed, the interaction went smoother if the robot also cast ‘human’ glances.

He did not achieve that effect in one go. “We first played test subjects ourselves quite often, but only when it felt natural to us did we really start testing,” says Mishra. “We also encountered practical issues. If the data shows that the robot has to look at something within 200 milliseconds, then the robot’s mechanism must of course be able to do that.”

Expressing emotions

The second part of Mishra’s research focused on the expression of emotions. The fact that these are the questions that science is now answering suggests that it will not be long before social robots appear in society. “It is often said that ‘in five years’ time the time will come’,” says Misha. “I can’t predict it. You now see all kinds of companies working on prototypes, so things are going fast. But the devil is in the detailsBefore you actually start using them, in healthcare for example, it must be thoroughly researched to ensure that it works as intended.”

Mishra now works as a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute in Nijmegen. “I would like to stay in science and combine research with teaching. I hope I get the opportunity to do that in India, so that more students can come into contact with AI and robotics there too.”