Anyone who throws away clothes also throws away memories. That is why Ted van Lieshout has been saving clothing for forty years: from his brother who died young, from his father, from himself… In his new poetry collection Sleeve me he brings them to life in words and images in seven chapters based on the motto ‘you are the soul of your clothes’, and gives them – the ‘clothes that have been abandoned’ and those who once wore them – a voice.

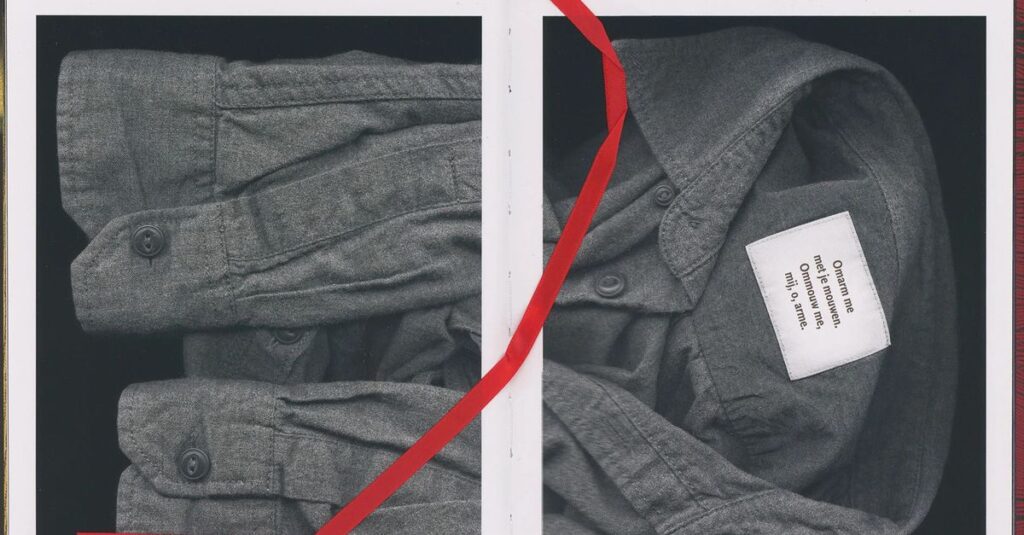

He does this in an inimitable way, playing unobtrusively and cleverly with the ambiguity and richness of the language, which is reinforced by the serene portrait photos of apparently casually abandoned clothing against a black background. The opening poem – ‘Embrace me/ with your sleeves/ sleeve me,/ me. oh poor one’ – which is playfully printed on a shirt label, immediately speaks volumes. The call for love and attention that arises from this is from a lonely person to an abandoned shirt, but also vice versa, and therefore undeniably mutual.

It is precisely this double perspective that gives the original poems and images their emotional expressiveness. This is also subtly reinforced by the well-considered composition of the beautifully designed collection: Van Lieshout arranged the chapters in such a way that a striking portrait of a growing child is created. Actually like he did before in Under my mattress the pea (2107), with the difference that the child in Sleeve me is closer to himself and at least partly stems from personal memory.

Gym shorts

For example, in the chapters ‘Cover me/ We want to wear’ and ‘Terlenka/ We are abandoned’, he writes with both wit and feeling about a sock that his grandmother knitted for him as a child: ‘Then she got rheumatism/ in her hands, halfway through/ the second. It was/never finished again’. And about a gym shorts that could have been a champion, “but/ he never won,/ because I was in it.” And about his father’s cap that he still has – ‘only,/ it doesn’t fit me. He’s too small./ How can a son’s head/ be bigger than a father’s?’

Later, the attention shifts to his deceased brother’s clothing. In the moving final chapters ‘Two brothers / We have been saved’ and ‘Final / Us’, pink children’s mittens remind him of winter brother adventures, a pajama top of the impending farewell, and purple-blue trousers of a past life: ‘Until now my brother has existed. / I stayed alone. I let him go./ He pulled away. I’m putting it on,” the label reads. Finally, the black leather jacket in ‘Look Around’ connects the present with the past and offers comfort: ‘Come home./ Take off your coat./ Hang it up.// Look back and see: that’s where/ your history begins.’

Not all poems are directly traceable. And not all poems are permeated with melancholy. Depending on who the garments belonged to, the tone is variously witty, moving, rebellious or titillating. For example, chapter five, ‘I am Ali / Seven pairs of jeans’, consists of a suggestive photo series of half-opened trousers, with the labels on the lines of the final, highly rhythmic evocative poem that celebrates a love game. (‘Come/ caress me/ steal me/ play me/ drag me// to your/ thieves’ den […]’). And here and there Van Lieshout even makes light social criticism in passing. In a poem about his old neighbor’s futile longing for death, the poet says meaningfully: ‘Compassion./ That is God but backwards./ […]/ You better pretend you don’t see people who want to die./ Look the other way./ That can never be a crime.’

In combination with the original perspective, this free approach to subject and form makes it unique Sleeve me a characteristic Van Lieshout: the collection of poems testifies to his drive for innovation and fits seamlessly with his artistic principle that every book must be a stand-alone art object made of language and images with due regard for the material. At the same time, Van Lieshout has put his soul into it, just like into those clothes. And you feel that: Sleeve me hits you right in the heart.