Once upon a time, it is not entirely proven, Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein were said to have had the following conversation. “What I admire most about you is your universal appearance. You do not speak a word, but the whole world understands you,” Einstein is said to have begun. To which Chaplin responded: “That’s right. But your achievement is even greater! The whole world admires you, while no one understands a word you say.”

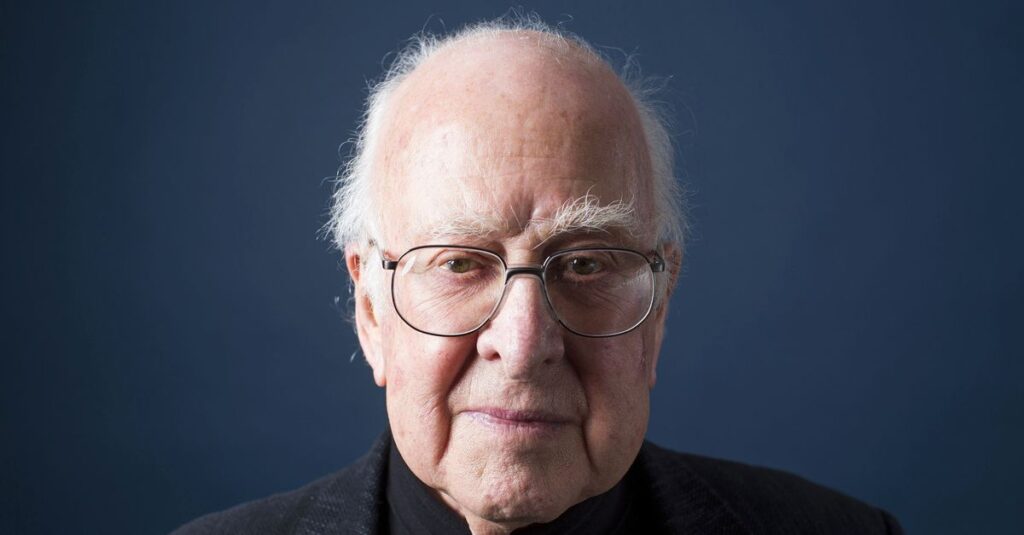

The latter also applied to Peter Higgs. His name buzzed around the world when the particle named after him was discovered in 2012 at the European Center for Particle Physics, CERN, near Geneva. It was in the headlines of the newspapers, echoed in television and radio news and flew over the internet. But like Einstein, only a select group of insiders understood what Higgs’ work really entailed.

In fact, Higgs was even more effective at achieving that brand awareness than Einstein. The latter developed the special and general theory of relativity, provided decisive evidence for the existence of atoms and helped make quantum mechanics great with disruptive ideas. Higgs’ fame, on the other hand, was based on just one article. In 1964 he described a mechanism that could explain why the building blocks of matter – stars, planets, people and camels – have mass and do not consist solely of energy.

And no, the idea for it did not come to him in a eureka moment, Higgs said in an interview in this newspaper in 2009. However, he knew in that summer of 1964 that he “had something.” And perhaps that is why he “out of absentmindedness forgot to take the tent instructions with him” when he went camping in the Scottish highlands with his American wife Jody Williamson. It was also pouring. So they ended up stranded in a bed and breakfast and ended their trip early, after which Higgs wrote the article at the University of Edinburgh that would make him world famous. “But I didn’t walk around shouting eureka.”

Bungler

With such anecdotes, Higgs often portrayed himself as a bit of a wimp. He was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in northeast England in 1929 to a Scottish mother and an English father who worked in London as a sound engineer for the BBC. He had asthma, so was often homeschooled by his mother, and the first thing he did when he went to secondary school in Bristol, who had since moved, was “to break my arm in a bomb crater.” [nog uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, red.] to fall.” More importantly, of course, he became fascinated by theoretical physics, partly because Paul Dirac, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, had gone to the same school in Bristol decades earlier.

But Higgs did not want to study at Oxford or Cambridge. “I think I was influenced by my family’s idea that the children of the idle and the rich wasted their own time and that of their teachers.” Instead he went to King’s College London and did his PhD in Edinburgh in the early 1950s. He also developed his theory in that city as an unobtrusive lecturer at the Tait Institute of Mathematical Physics in 1964.

Symmetry breaking

Space is filled with a ‘field’ that also includes a particle, Higgs proposed, just as a particle of light is inextricably linked to an electromagnetic field. The power of the field proposed by Higgs was that it broke the symmetry that initially makes all fundamental building blocks from the ‘standard model’ of matter massless. Such a ‘spontaneous symmetry breaking’ has been compared to the asymmetry of grain in wood. In that image, light particles travel in the direction of the nerves and thus experience no hindrance along the way. Mass particles travel perpendicular to the grain and therefore become slow and ‘heavy’, like the matter that makes up planets, stars and people.

It was not an idea that was immediately accepted and it also took a while for that ‘symmetry breaking’ to fully crystallize. A first version of Higgs’ article on the mechanism was even rejected by the scientific journal Physics Letters. The editor of that journal published at CERN did not see what “its relevance to physics could be.” That’s his advice to give it a go Nuovo Cimento was “not very polite,” Higgs discovered only later: “Nuovo Cimento posted all submitted articles without peer review.”

Additional paragraph

Yet the rejection was a blessing in disguise, because to demonstrate the relevance of his work, Higgs added an extra paragraph. Precisely there he wrote that the field he proposed could produce an associated particle, a so-called boson. And it was precisely that idea that attracted attention, according to Higgs himself, when the revised article was accepted by the American scientific journal Physical Review Letters. So much so that it overshadowed the publications of five other physicists: François Englert and Robert Brout of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel had not mentioned the boson in their publication on the same mechanism published six weeks earlier. The elegant work of the British Tom Kibble and his American colleagues Carl Hagen and Gerald Guralnik, published slightly later, also faded into the background.

But just as important was probably that a year after publication, Higgs traveled to the United States during a sabbatical and brought his work to attention there almost monomaniacally. Higgs was fortunate that, as a visiting scholar at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he was invited by the flamboyant physicist Freeman Dyson to present his work at Princeton. The new invitations this brought him, including from Harvard, then took Higgs from university to university. It cost him his marriage to Williamson, who had meanwhile given birth to their eldest son in Illinois with her parents, but Higgs’ work was firmly on the map.

Wrong way

In later years, when his work was recognized and known, Higgs was the first to mention how many people and how much thinking had been needed to really make the ‘Higgs mechanism’ fall into place. He invariably talked about how much he was initially inspired by the work of the American-Japanese Yoichiro Nambu and the American Phil Anderson. He emphasized that he himself had first looked in the “wrong direction” when, when applying his mechanism, he had only thought of ‘hadrons’, very popular particles at the time that were subject to the so-called strong force. And he explained that the Higgs mechanism would ultimately prove its strength in the electroweak theory. It was developed by Nobel Prize winners Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, while the Dutch Nobel Prize winners Gerard ‘t Hooft and Martin Veltman had laid a solid foundation for it in the early 1970s.

Particle collider

The fact that thousands of physicists and technicians then made efforts to capture the Higgs boson associated with the Higgs mechanism, starting in the early 1980s, did not seem to make Higgs very nervous. Work lasted more than a quarter of a century on the gigantic Large Hadron Collider particle collider and on measurement setups as large as cathedrals, with parts more refined than gossamer lace. The particle had to show up there, Higgs thought. If that didn’t happen, he said rather laconically in 2009, “I would no longer understand anything about the entire field (…) that I thought I had finally understood.”

Higgs himself had been leading a retired life in Edinburgh for years. Since his divorce in the early 1970s, he lived alone in an apartment in the old center, without television, mobile phone or use of social media, but with a collection of jazz records. His sons Chris and Jonny, computer experts and jazz musicians, lived nearby, as did Williamson, until her death in 2008. It was a beautiful coincidence that just a stone’s throw away, more than two hundred years earlier, James Clerck Maxwell, who later attended King’s College, had been born had anticipated the electroweak theory in London when he brought all electrical and magnetic phenomena under one denominator.

Not very spectacular work

Higgs, who continued to work at the University of Edinburgh until his retirement in 1996, had done little spectacular work in physics. He was a physicist of the ‘one big idea’, just like, for example, quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger was. He even stated at the BBC that “if he had not been nominated for a Nobel Prize, he would have been fired long ago for lack of productivity.”

When he won the prize in 2013, he shared it with François Englert and celebrated it at CERN, where experimental proof of the Higgs boson had been provided. According to the Nobel regulations, Brout could not share in the honor because he had already died. The work of Kibble, Hagen and Guralnik, published just a little later, also fell by the wayside. Higgs’ life also illustrates the erratic role of chance and luck in science.

Correction April 10: An earlier version of this article stated that Higgs shared the Nobel Prize with CERN. He shared it with François Englert, and celebrated it at CERN.