The xoanon is a statue, a wood carving of an armed female figure, not particularly beautiful, in fact it is a refined beam or plank. But it’s not about the superficial appearance, it’s about the sacred meaning that is attributed to it.

Then the unsightly thing suddenly becomes special, because the thing is said to date back to ancient Troy. And the xoanon ‘offered the city protection for as long as it remained within its walls’, according to tradition. So it depends on how you look at it: are symbols intrinsically worthless, or are they ‘all condensed meaning’? The skeptical Jon Beaujon, the novel’s main character The xoanoneperhaps should also recognize that symbols ‘have the power to inspire the people, to move the masses and to bring about revolutions’.

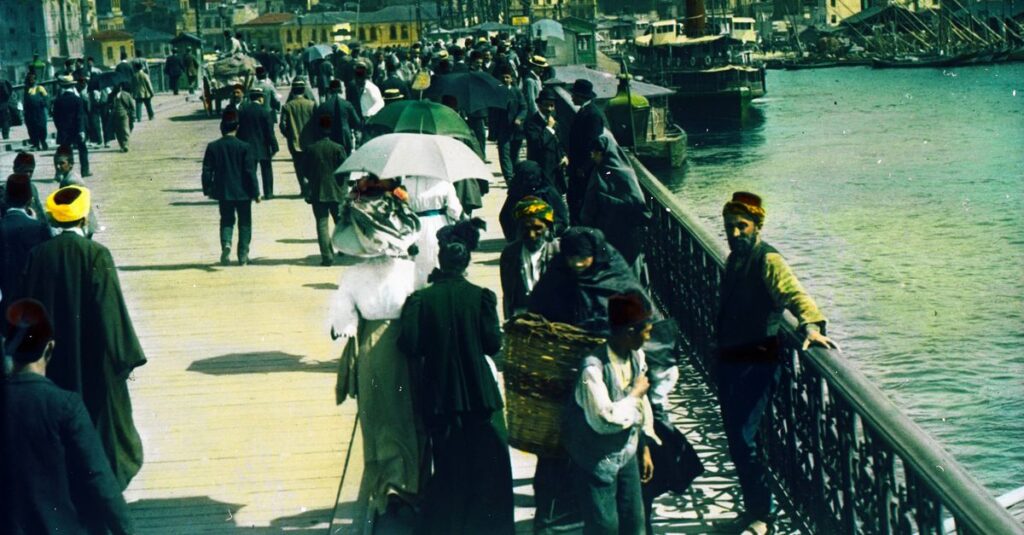

And movement, revolution, that’s what he’s up for. “I was looking for a powder keg to light a fuse in,” he begins his story, and that promises something. He is in Constantinople, just after the First World War, a city of ‘unclear denominations, staggered border lines and identities, of ambiguous loyalties and underground networks’, as Jan van Aken describes it. Today’s Istanbul is still divided into sectors under different supervision, like post-war Berlin, the global superpowers are trying to assert their influence. And Jon Beaujon came for the accompanying dark rustling and scheming, because: ‘Nothing has been determined yet, everything is possible.’

Also read

this review

/s3/static.nrc.nl/bvhw/files/2024/03/data113591983-f035c2.jpg)

Our main character gets out of bed for that, literally, because he scours the alleys, brothels and clandestine cafes, especially at night. He is the type of adventurous schemer with which the reader of Jan van Aken (1961) is familiar. His oeuvre – think of his last two novels The Apostate (2013) and The procession (2018) – is populated by villains who live in historical focal points and pull sensitive strings, although they themselves remain out of harm’s way.

Flutter property

Van Aken’s new protagonist also has that, that fluttering quality that you could associate with a sovereign kind of Britishness: in splendid isolation drinking a cup of tea while everything collapses around him. Unmoved and unobtrusive, but still interesting. On nights out he does his best to ‘be a sparrow among birds of paradise’. Always incorruptible, as in this sentence: ‘For lack of a hand grenade I gave them a smile.’

But in the meantime! Jon Beaujon is not who he says he is and he sometimes gives us a glimpse of the mystery. He mentions that he ‘naturally has a special interest in the role of Albion’, that he is concerned about not being recognised, that his ‘slight Dutch pronunciation is credible enough’. [moest] his’… That mystery puts the first hundred pages under tension, which immediately shows one of Van Aken’s qualities: he can let anything happen beneath the surface.

And, importantly, forging a bond with the reader. He feels initiated, (intellectually) challenged, because he knows that ‘Albion’ stands for Great Britain, understands how a ‘wisp of pigment spots, liberally sprinkled across his face, was reminiscent of a map of the Dodecanese’, and can chuckle when ‘a layered fluid of spirits’ comes out of someone’s mouth, which Van Aken does not explain further. That innuendo is a style choice, but also a substantive principle The xoanone: in the tangle of scheming, one listens unaffectedly to surprises and incongruities all the time, while nodding understandingly. Either everyone really knows what’s going on all the time beneath the surface, or everyone keeps up appearances – but hey, which is it? Van Aken also uses this ambiguity to unleash the hunt for that xoanone in full earnest: Van Aken gives the Indiana Jones-like quest the air of something with great geopolitical weight.

As a reader you go along with this to a great extent, expecting that the novel will have a great impact. You get hyped up with the characters who are after that xoanone and make all kinds of important things about ‘small changes that can lead to chains of events, which in turn propagate quickly, sometimes even exponentially’. So pay attention, in the chaos that the novel has quickly become. Beaujon bounces around the city like a ball in a pinball machine, from one chance encounter to the next, and keeping track of who is who requires a lot of attention and Ausdauer, let alone which side who is on and who wants what.

Fortunately, Van Aken writes well, pointedly, with occasional room for humor that makes things banal and manageable again (‘The dromedary in the bushes made a sound that my mother would have honored with a slap in the ear’) and visual description ( ‘The crowd waved and writhed and engulfed the reluctant undesirables in a distorted peristalsis in order to expel them’). And yet you don’t really know where you have ended up, two-thirds of the way through the novel, when Beaujon comes face to face with an old drug dealer in a wheelchair with locking wheels, smoking a Cuban cigar against the foul stench of a rotting corpse in a pool of blood next to him.

War trauma

Entertaining, but for what purpose? That’s the downside of the wink-wink-nudge-nudgestyle of Van Aken: that as a reader in your own spy life, after another soiree and another chase, you never even receive confirmation from headquarters that you are on the right track. “I got the nasty feeling that she was trying to reenact a scene from a bad movie,” Jon Beaujon confides to the reader at one point: recognizable. ‘Don’t you see the pattern? You are in fact following the corridors of a mystical labyrinth’; there is a limit to that belief.

Is it strategy or chaos, what does this book want? What is Beaujon actually aiming for, you wonder: his great hatred towards the British superpower, thanks to a war trauma, turns out not to be such a strong motivation after all (and that hated British character has long since been internalized by this proto-James Bond, I would say). There lies quite a missed opportunity for a convincing psychological motif in the novel. And what about the geopolitical aspects? That everything is possible is an illusion, that there are any strings to pull may be, and Beaujon’s need to protect the American reporter Iliana seems to have rather banal motives. That the Trojan statue represents value for the soldiers who flood Anatolia: what did you think?

Does that perhaps represent Van Aken’s view on geopolitics? That everyone runs diligently after something sacred, but when a headless chicken ends up in total chaos, they then drop the scales from their eyes and save what can be saved, enjoying the spectacular view? That also seems like the right reading attitude to me The xoanone to persevere to the end: a snob sometimes wants to ride the roller coaster. But does that represent anything meaningful?